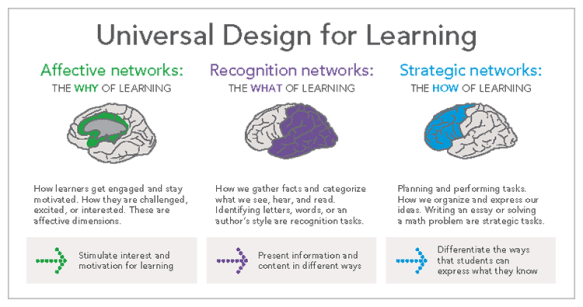

This week’s blog reflects on several articles that discuss the implementation of the UDL framework and effective application of UDL into instructional practices at the post-secondary level.

UDL on Campus…A CAST Initiative

College STAR (Supporting Transition, Access, and Retention) is an initiative out of the University of North Carolina system that builds models of student and faculty support to address learning differences, specifically learning disabilities and ADHD. This initiative, currently at the North Carolina Greensboro, Carolina University, Appalachian State University, and Fayetteville State University campuses, focuses on UDL as part of a model to make educational environments more welcoming for a wider variety of learners.

A network of support is provided for students who historically have slipped through the cracks — students who are capable of college success but often struggle academically because they learn differently. By weaving together direct supports for students, instructional supports for faculty members, and partnerships with public school professionals, this initiative is providing the opportunity for participating campuses to learn together and implement effective strategies for teaching students with varying

learning differences in post-secondary settings.

Strengths in the program:

- A clear mission throughout each college campus with a two-fold focus — direct student support to students within our specific target population and a campus-wide focus on UDL to benefit all students;

- The programs are not cookie-cutter but instead designed with each specific campus mission, culture, and priorities in mind;

- A commitment to shared learning that permeates throughout the College STAR initiative, and a project-wide evaluation model guides our work together; and,

- Unwavering belief in the effectiveness of UDL…instructional development support, for faculty who teach increasingly diverse groups of learners in today’s college classrooms, is grounded in principles of Universal Design for Learning (“About,” n.d.).

Services available through College STAR student-support programs include:

- assistance in making the transition from high school to college;

- seminar-style courses to equip students with skills necessary to succeed in their other coursework; and,

- a support network that includes advisors, mentors, tutors and/or specialists (“College Star,” n.d.).

Participants are encouraged to explore a wide range of assistive technologies that may help them with their coursework (“College Star,” n.d.). Tutors are a key part of the program and work closely with faculty members, attend classes for which they are providing tutoring, and hold group and individual peer tutoring sessions for undergraduate students (“College Star,” n.d.). Tutors also receive training in learning theory, learning differences, and use of assistive technologies (“College Star,” n.d.).

College STAR provides support for faculty members who want to infuse the principles of Universal Design for Learning into classroom instruction and each university has designed an instructional support model for faculty members. Faculty development modules and case studies (n.d.) in the College STAR program are quite extensive and include:

- Active Collaborative Quizzes

- Advance Organizaters

- Charting Student Information

- Classroom Response Systems

- Collaborative Learning

- Creative a Welcoming Learning Environment

- Flipped Classroom

- Game-Based Learning

- Inquiry-Based Learning

- Lecture Capture

- Livescribe Pen

- Merging Silly and Serious for Creative Expressions of Learning

- Mnemonic Devices for Instruction

- Padagogy Wheel

- Promoting Student Engagement

- Read and Write

- Team Based Learning

- Using iPad for Preserving Class Information

- Using Organization to Streamline Courses

- Uses Quizzes to Increase Compliance

- Using Syllabi to Organize Courses

- Using Web 2.0 Tools to Engage Learners

- When Lecture Is Necessary

- Writing for the Right Audience

EDUCASE: 7 Things You Should Know About UDL

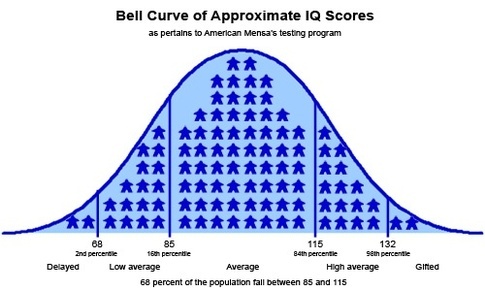

There are key considerations to keep in mind to establishing successful UDL systems change initiatives in higher education. Learner variability is the rule, not the exception. Using the UDL framework to design courses and learning environments can be daunting and leave professors feeling overwhelmed but even changing one or two practices or materials can help build momentum (“Getting Started,” n.d.). Support from administrators and the university can assist professors as they begin the task of implementing UDL in their courses (“Getting Started,” n.d.). The video on the UDL on Campus website advises getting started in small steps because it’s not necessary to make sweeping changes all at once. We need to remember that UDL implementation is a dynamic process.

The Educase article (2015) begins with a scenario:

A committee is seeking to reduce the number of withdrawals from the college’s intro courses. Because these high-enrollment courses tend to have multiple requests for accommodation from students with disabilities, a consultant recommends implementing UDL and the committee decides to to redesign one history course as a pilot.

When polled about the course design, students appreciated the value of the flexibility in learning activities (e.g. multiple means of representation) and testing (e.g. multiple means of action and expression). At the end of the semester, the college finds that grades were 12 percent higher than in the other intro history courses, requests for special accommodation dropped to zero, and course withdrawals were cut in half.

As noted in both the video and scenario above, UDL implementation is a dynamic process and it’s not necessary to make sweeping changes…it can start with small steps.

The Educase article (2015) suggests additional considerations when establishing successful systems change initiatives in post-secondary settings:

- Professors need initial and ongoing support to implement UDL in their courses. One example of support includes a website for faculty, students, and student advocates, where instructors can find help teaching a class that includes students with disabilities and students with learning differences can find self-advocacy resources.

- UDL challenges the status quo: This could mean that faculty, designers, and administrators face difficult conversations as they integrate UDL into the learning environment.

- A campus-wide adoption of UDL can be expensive, and a full picture of the costs and benefits of UDL—including the retention of students who might otherwise not return—should be developed.

- It must be made clear that UDL does not lower expectations but opens new learning pathways that can help more students meet existing expectations.

- Adoption of UDL can help an institution commit to a broader range of students, cultures, abilities, and backgrounds.

- For faculty, the prospect of teaching effectively to all learners is rewarding, particularly when it is visibly demonstrated that more students are able to succeed.

- UDL has been effective in addressing such troubling issues such as student apathy, sinking enrollment, and rising dropout rates by ensuring that students have equal access to learning and participatie in their own education.

- A campus-wide adoption of UDL can be expensive, and a full picture of the costs and benefits of UDL—including the retention of students who might otherwise not return—should be developed.

- Although many institutions turn to UDL initially as a tool for meeting the legal requirements of ADA compliance and optimizing the tools of assistive technology, UDL’s focus on reducing physical, cognitive, and organizational learning barriers goes beyond students with disabilities and provides support for and accommodates the differences of ALL students.

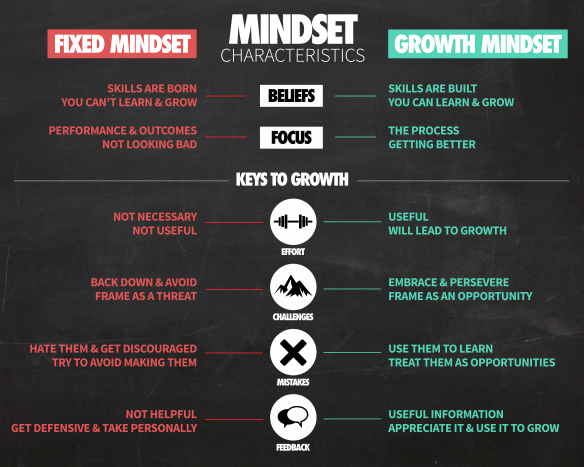

As schools at the K-12 level implement UDL with the goal of creating expert learners, post-secondary education should also have the same goal for their students:

In the best learning environments, where students are exposed to a variety of learning paths, multiple means of action and expression, and opportunities for engagement, they come to recognize their own best approaches for self-education and sustainable learning, and become expert learners (Educase, 2015).

UDL in the College Courses and Post-Secondary Education

UDL is becoming more established in K-12 education but is much newer to higher education. Rose et al. (2006) state that “UDL requires that we not only design accessible information but also accessible pedagogy” (p. 2).

Pedagogy is the science of teaching and learning—the educational methods that skilled educators use to highlight critical features, emphasize big ideas, clarify essential relationships, provide graduated scaffolds for practice, model expert performance, and guide and mentor the apprentice (or student) (Rose et al., 2006).

In Universal Design for Learning in Postsecondary Education, Rose and his colleagues note two important points: research and application still lag behind theory with respect to UDL in university settings and implementing UDL in college courses is rare, especially at the graduate level.

The authors then discuss attempts to apply UDL to an existing Harvard University graduate course. Rose and his colleagues tell us that the course description communicates an obvious goal: to teach information. The authors share that UDL tells us that it’s not enough for students to acquire information — they must also have some way to express what they have learned and some way to apply that information as knowledge (thus, making knowledge useful). Furthermore, there is an affective component to learning goals:

- Students will never use knowledge they don’t care about, nor will they practice or apply skills they don’t find valuable; and,

- Students need to be fully engaged in learning the content, to be eager to apply what they know, to leave the course wanting to learn even more, and to want to apply their knowledge everywhere (Rose et al., 2006).

Lectures and textbooks are typical in college courses. While the content and the language in a lecture are best conveyed and accessible in a printed version, the expression capacity of the human voice – its ability to stress what is significant and important, to clarify tone and intent, to situate and contextualize meaning, and to provide an emotional background – is a strength of lectures (Rose et al., 2006). Rose et al. (2016) share that good lecturers also use facial expression, gesture, and body motion to further convey meaning and affect, and that lectures combined with additional media provide students with a rich multimedia experience. Lectures play an important role in the Harvard class and many other college courses as well, but there are still barriers to learning to overcome and that can be accomplished by utilizing multiple means for representing information. One example, used in the Harvard class, is videotaping lectures:

- Students can access the lecture at any time;

- Information is more accessible for some students than the live lecture;

- Video’s flexibility allows students to replay it entirely or stop and start segments; and,

- Learning is more accessible through a video for those who struggle with sustained attention and concentration during live lectures (Rose et al., 2006).

The Harvard class also collects student notes from the lecture and provides them to all students enrolled in the course (Rose et al., 2006). There are several unexpected benefits to this. Some students take very detailed linear notes, others take very graphic notes with little text, and others run the gamut in between the two. Students notes represent differences in notetaking or in other words, learner variability. Also, students often enhance their notes knowing they are going to be publicly posted to be shared with classmates (Rose et al., 2006). Rose et al. (2006) state that what becomes clear from a UDL perspective is that although a lecture conveys course content to the students in the Harvard class, reception of the material is highly variable due to learner variability. The authors talk about additional options provided in the Harvard class: discussion groups, review sessions, and advanced sessions that can supplement lectures and compliment textbooks. Furthermore, there is a course website that contains the syllabus (multimedia with links and media), the assignments, the discussion groups, the projects, the class notes, the class videos, and the PowerPoint slides for the lectures, along with links to many websites that are additional representations of the topic for the week, or as scaffolds and supports for student learning.

Barriers and the challenges of individual students can’t be considered “individual” or student problems because that view promotes solutions that address weaknesses in the individual (Rose et al., 2006). Using a UDL lens, these issues should be considered “environmental” problems in the design of the learning environment.

Unfortunately, universities place too much emphasis on students’ disabilities and not enough on the disabilities of the learning environment (Rose et al., 2006).

References

About College Star. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.collegestar.org/about

College Star Frequently Asked Questions. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.collegestar.org/frequently-asked-questions#what-is-the-college-star-program

Educase. (2015). 7 Things You Should Know About UDL. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/~/media/files/library/2015/4/eli7119-pdf.pdf

Faculty Development Modules and Case Studies. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.collegestar.org/modules

Getting Started. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/udl_gettingstarted#.Wteq0y7wbIU

Legal Obligations for Accessibility. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/policy_legal#.WtevHi7wbIU

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19(2), 17.