Normality and the Mythical Average Learner

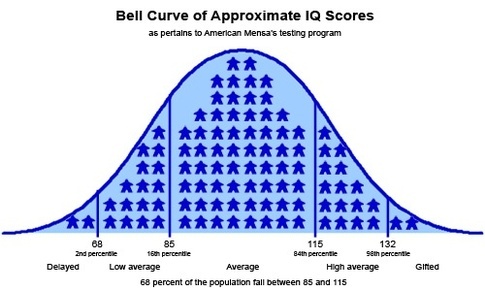

In The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (Hernnstien & Murray, 1994) and Real Education (Murray, 2009) , Charles Murray argues that human behavior — including IQ — distributes along a bell-shaped normal curve and that intelligence is fixed.

-

©www.greyenlightenment.com

Dudley- Marling and Gurn (2010) state that the theory of the normal curve, when applied to education, affects school placement, grading, college admission, educational policy and research, and teachers’ approach to instruction and learning. The authors argue that, “not only is the normal curve is not normal, the idea that human behavior distributes along a bell-shaped curve with most people clustered around the mean or average grossly oversimplifies the diversity of human experiences” (p. 3). In addition, they note that the human experience is infinitely complex and that equating students with scores on a distribution, averages, or statistical norms ignores the complex systems of which students are a part (Dudley- Marling & Gurn, 2010) — a variety of educational staff, other students, and a myriad of learning environments.

The concept of normality, in which human diversity is characterized by a bell-shaped curve and populations are viewed around the idea of a statistical norm, is one of the most powerful ideological tools of modern society…there is probably no area of contemporary life in which some idea of a norm, mean, or average has not been calculated (Dudley- Marling & Gurn, 2010).

Learner Variability and the Expert Learner

The philosophy of normality and fixed intelligence only lends itself to the idea of the “mythical average learner” and ignores human diversity and learner variability. The UDL framework allows educators and school systems to focus on learner variability and creating expert learners.

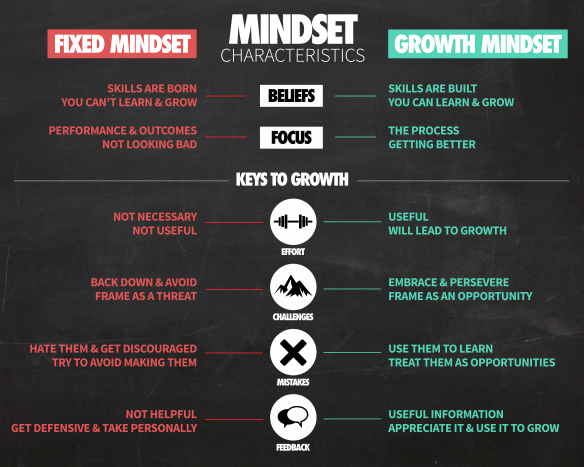

But what is an expert learner? First, let’s look at the concept of expertise. Expertise is never static but rather a process of continuous learning…of becoming more motivated, knowledgeable, and skillful (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014). Given the variability of learners and learning contexts, expertise looks different from person to person. Meyer et al. (2014) note that while the mastering of specific content and skills is still important, there should be an emphasis on process rather than product. Furthermore, they posit that learning expertise cannot be measured simply by evaluating competencies and outcomes at a single point in time because learning is a process of continuous change and growth.

We define expertise not as a destination — signifying the mastery of content knowledge and skills — but rather as a process of becoming “more expert” on a continuum of development…(Meyer et al., 2014).

Everyone can become an expert learner because everyone can develop the motivation, practice, reflection, self-efficacy, self-regulation, self-determination, executive functioning, comprehension, and situational awareness that help make experts what they are (Meyer et al., 2014). The authors argue that what makes expert learners experts is not content knowledge, but their ability to recognize where they are challenged, their motivation to overcome difficulties, and their skill at seeking out and using strategies to reduce or overcome barriers. Meyer and his colleagues offer learners several excellent questions to reflect on:

What are my strengths and weaknesses? What is the optimal setting for me to learn? Which tools amplify my abilities and support my areas of weakness? How do I best navigate my environment? How do I best learn from peers? How can I support myself when I feel anxious about an upcoming challenge? How can I be open to unlearning mistaken or outdated understandings and build new ones? How can I learn from my mistakes?

Thus, the key to expert learning is self-knowledge as a learner — an awareness of one’s strengths, challenges, and needs — and it is this self-reflection, an essential practice of expert learners, that personifies the growth mindset (Meyer et al., 2014).

Meyer, Rose, and Gordon (2014) note that expert learners are not created in a vacuum. While teaching is an inherent part of who we are and central to everything we do, they argue that expert learners require expert teachers who need to be expert learners themselves. The authors suggest that teachers need to cultivate their own development as teachers, embrace change, and continuously appraise their own work and their students’ progress and adapt on the fly. Furthermore, the authors state that the development of students and teachers as expert learners requires us to design educational systems to be expert systems – communities of practice – where expertise is valued, nurtured, and developed for educators and students both. Learning environments need to be smart and flexible enough to support expert learning which, in turn, requires that all parts of the system – students, educational staff, and school systems – work together as a flexible, supportive community and support the goal of learning expertise for all (Meyer et al. 2014).

Thus, Meyer and his colleagues (2014) champion UDL because it provides a framework to develop expert learners, expert teachers, and expert systems and assists educators in creating expert learners…learners that have become purposeful and motivated, knowledgeable and resourceful, strategic and goal-directed.

Learner Variability, Barriers, and Expert Learners in an Instructional Setting

When reflecting on these topics, my daughter and a particular instructional setting came to mind. A college sophomore, Shannon was taking Introduction to Sociology last semester. She shared with me that her professor was a young sociologist, an adjunct professor with little teaching experience. Shannon was one of 50 students. This class was a liberal arts requirement, the type of course which lends itself to larger numbers of students and faculty with less experience. Early on in the semester, my daughter bemoaned the fact that the professor mostly lectured from a PowerPoint presentation and pretty much read off the slides. Even though part of the grading rubric included points for participation, this professor did not stimulate conversation often. Tests were the only evaluative tool. My daughter was bored, not engaged, and unmotivated.

Let’s first reflect on the learner variability present in this classroom. There are 50 learners, each with different learning styles, competencies, strengths, talents, and needs. Variability goes far beyond that to include gender, culture, language, disability, economic background, previous schooling (e.g. public, private, parochial, charter school), past curriculum (e.g. IB, AP, honors, college preparatory, remedial classes, special education instruction), and study and organizational habits. And let’s not forget about past learning experiences – positive and negative experiences along with great and not so great teachers – that influence motivation, anxiety, stress, and other emotional responses connected to the affective networks of the brain. Learning is emotional work whether for students or for teachers (TU Office of Academic Innovation, 2016).

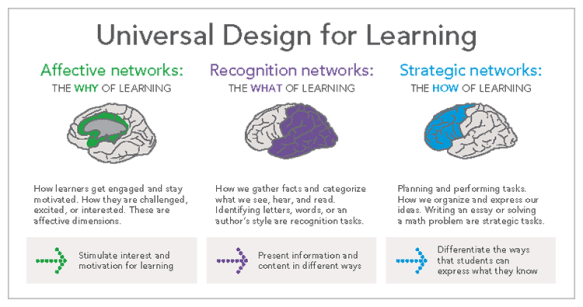

Meyer, Rose, and Gordon (2014) share that each person’s brain is unique just as their fingerprints are. Modern neuroscience is deeply relevant to education and provides insight into the nature and origins of learner variability (Meyer et al., 2014). The authors note that although learners are unique, they share common, predictable patterns of variability in the affective, recognition, and strategic networks of the brain.

- ©National Center on Universal Design for Learning

These 50 different learners bring to this class a variety of ways in which they:

- are engaged, stay motivated, challenged, excited, or interested (Affective Networks);

- gather facts; categorize what they see, hear, and read; or identify letters, words, or an author’s style (Recognition Networks)

- plan and perform tasks, and organize and express their ideas (Strategic Networks)

Each one of these 50 students is unique and learn in ways that are particular to them (Meyer et at., 2014). The suggestion of broad categories of learners is a flagrant oversimplification that does not reflect reality (Meyer et al., 2014). Looking at one’s class roster as simply 50 students is a distorted view when considering teaching style and delivery of instruction. Learner variability is much more complex and calls for the use of UDL principles when designing instruction. Ways to improve the instructional setting for these students include:

- Engagement – Play classical music at the start of and/or throughout class; provide feedback during discussions, other class work, and outside of class; teach simple techniques to help manage emotions; hold class outdoors; offer small group work (collaborative learning); invite guest lecturers, and plan field trips.

- Representation – Utilize presentations and lecture notes with visuals, music, embedded links and digital media; videos; websites; online and printed versions of textbooks; podcasts; and connect content to art, literature, film, music, science, history etc.

- Action and Expression – Provide options such as reflection papers, tests, blogging, video blogging, presentations, videos, online and in class discussion, and other assignments designed to be collaborative and allow students to show the application of their learning.

This learning environment is a far cry from a dry PowerPoint lecture and exams. It is more dynamic and engaging, and will help to remove barriers associated with the three networks of the brain and address:

- affect (emotional regulation) → Affective;

- the recognition strengths, needs, and preferences of learners → Recognition; and,

- the variability in and promotion of the acquisition of executive functions which are important higher level skills including planning, organizing, progress monitoring, constructing alternative strategies, and seeking help → Strategic (Meyer et at., 2014).

Thus, the goal is to design a flexible learning environment to address the variability of learners in this instructional situation and become expert learners — learners who know how to learn and how they learn, and can apply those skills to other contexts including other courses, learning environments, and experiences after they leave Introduction to Sociology (Digital Promise, 2017).

References

Digital Promise. (2017, March 8). Research@work: Embracing learner variability in schools. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BxLz_fSvBqU

Dudley-Marling, C. & Gurn, A. (2010). The myth of the normal curve. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Hernnstien. R. J. & Murray, C. (1994). The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American Life. New York, NY: Free Press.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional Publishing.

Murray, C. (2009). Real Education. New York, NY: Crown Publishing.

TU Office of Academic Innovation. (2016, May 14). Universal design for learning: Variability in emotion and learning. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LDaP-THd-9c&feature=youtu.be